Tag: wireless

-

scanlime:005 / Microphone Receiver

I take apart a Pyle PDWM1940 wireless microphone receiver, searching for a way to make the output less noisy. Meanwhile, I’ll be using the same receiver for filming.

-

Hacking My Vagina

To me, a good sex toy helps form feedback loops. It doesn’t get in the way. A good toy gives you simple ways of exchanging signals with a partner or with your own body. It acts as a conduit. A good sex toy is analog.

-

Propeller Bluetooth Stack Demo

After going months without a lot of time for working on my hobby projects, I finally had a few free days to work on debugging my embedded Bluetooth stack for the Propeller. I got it working well enough to demo a Serial Port Profile device, implemented using only a Propeller Demo Board and a $2…

-

Embedded Bluetooth for $2

This is a continuation of my experiments in bit-banging full-speed USB on the Propeller. I have the basic host controller working reasonably well now, so I started trying to do something a bit more “useful” with it by implementing a simple Bluetooth stack on top of it. Bluetooth and USB are both quite complicated, and…

-

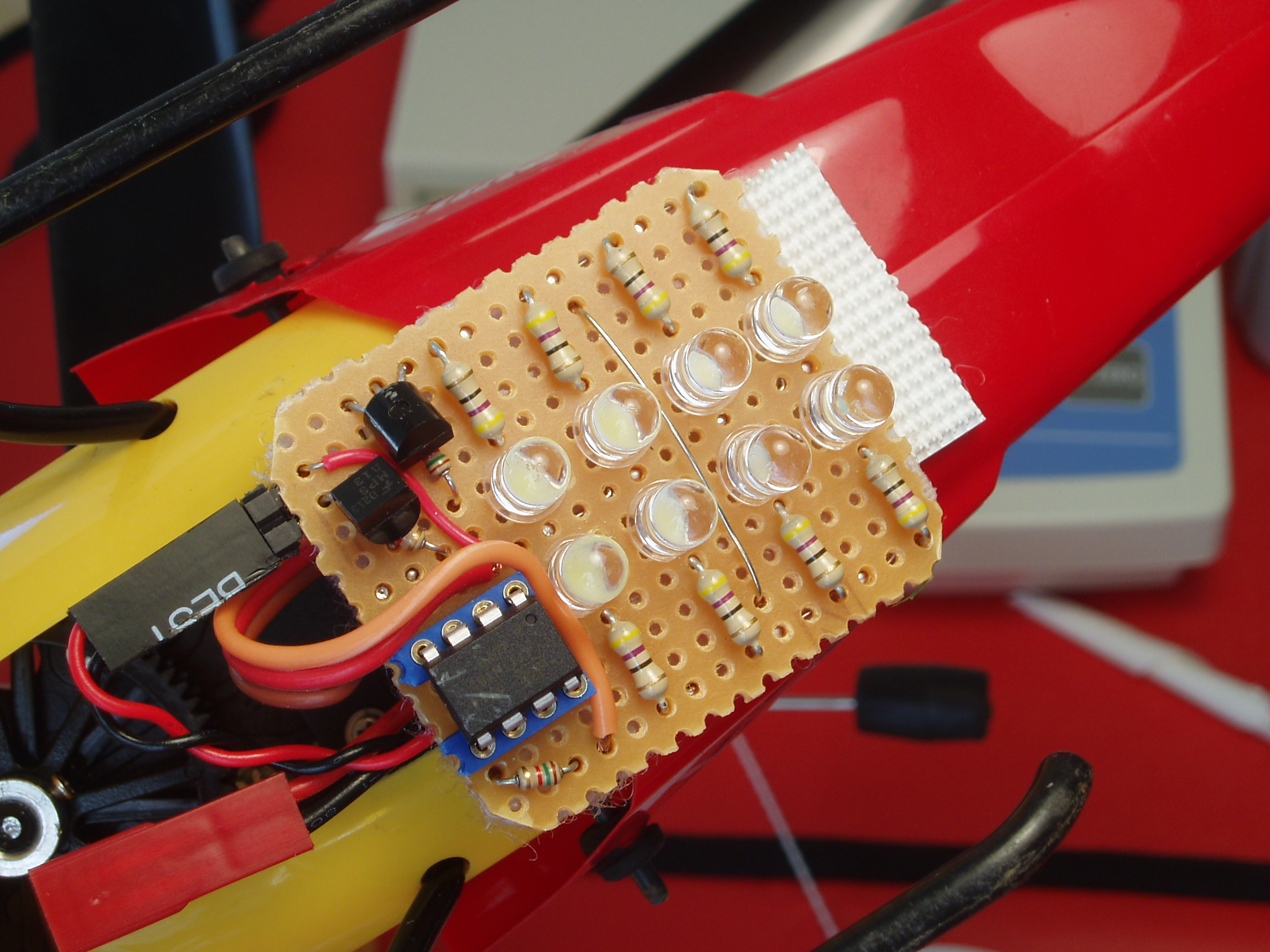

Hardware sketch: R/C helicopter light kit

As great as it is to finish a professional-looking hardware project with optimum component choices and full design documentation, I love the feeling of sketching in hardware (or as I’ve called it in the past, improvisational electrical engineering). Despite all the faults and rough edges in today’s development tools, we do live in a world…