Tag: assembly

-

scanlime028 – Four Winches

Continuing our Tuco Flyer robotic camera project, this montage covers the remaining electronics assembly and bot calibration to get our winches flying a 1.5kg spool around the shop! Music for this episode is “Something Elated” by Broke For Free, licensed under CC BY 3.0, remixed slightly. Please consider supporting me on Patreon so I can…

-

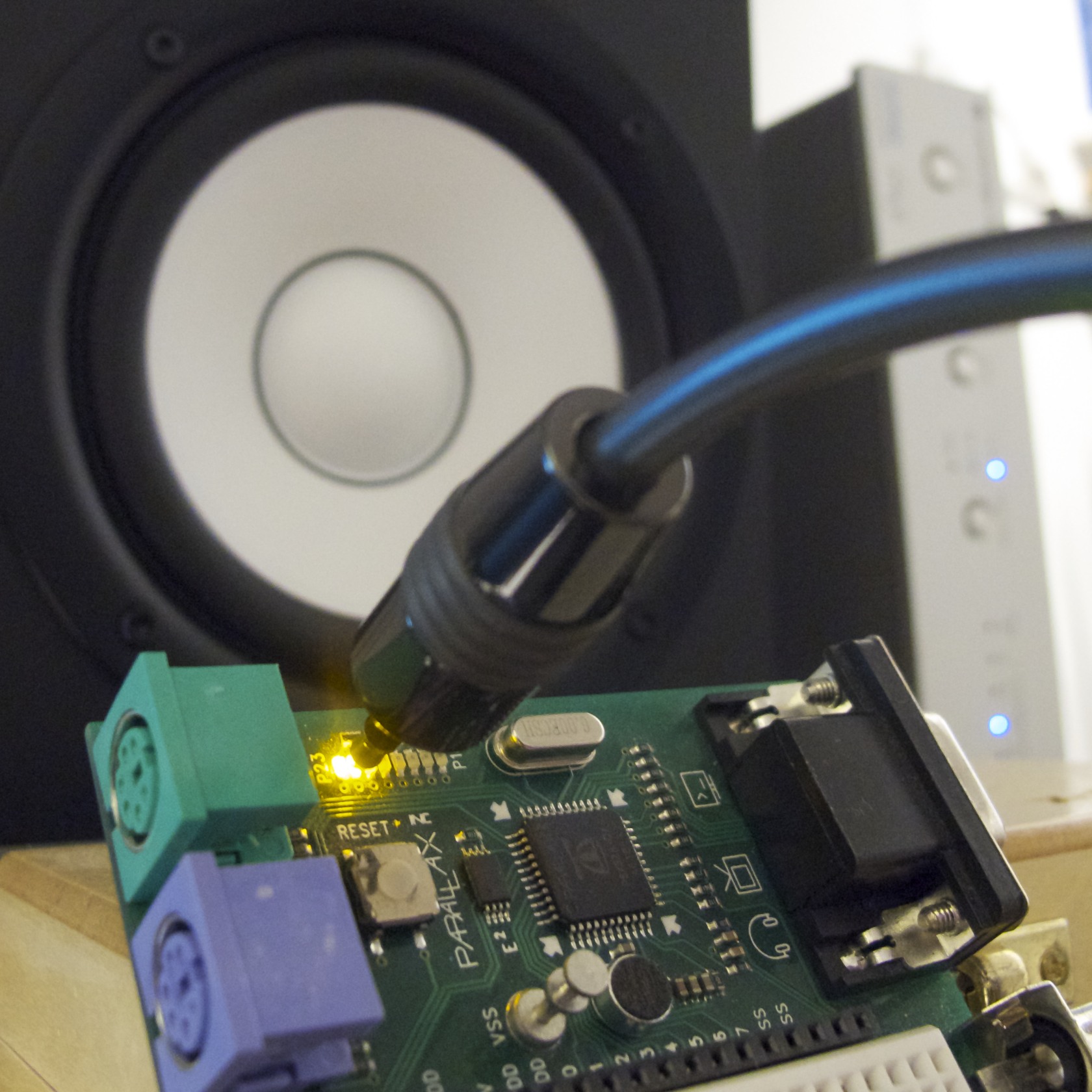

S/PDIF Digital Audio on a Microcontroller

A few years ago, I implemented an S/PDIF encoder object for the Parallax Propeller. When I first wrote this object, I wrote only a very terse blog post on the subject. I rather like the simplicity and effectiveness of this project, so I thought I’d write a more detailed explanation for anyone who’s curious about…

-

A Binary Patch for Robot Odyssey

Robot Odyssey is one of the games that I have the fondest childhood memories of. It’s both a high-quality educational game, and a gentle (but very challenging) introduction to digital logic. There’s a Wikipedia article on the game. There’s also DroidQuest which is a Java-based clone of Robot Odyssey. The DroidQuest site also contains some…